Robert Aldrich’s 1962 horror thriller Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? single-handedly spawned the psycho-biddy subgenre by successfully blurring the thin line already dividing the gossip column-generating heat of off-screen rivalries indulged at the time -- largely for publicity purposes -- by its two ageing Hollywood stars, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, and the murderous, co-dependent animus that drives the unstable characters they play to extremes within the context of the film itself. The imaginations of movie audiences were galvanised by the histrionic performances delivered by these rival ‘Grand Dames’ of the silver screen amid the feverish atmosphere of stifled Gothic melodrama Aldrich was able to generate from Lukas Heller’s adaptation of Henry Farrell’s source novel. It was inevitable a second pairing of the veteran star actresses and the independent director would become a much sought-after commodity in the wake of the unexpected box office success and the five Academy Award nominations picked up as the fruits of their first collaboration, and so when Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) came along, 20th Century Fox must have been banking on the chance to considerably up the ante on its Warner Brothers-distributed predecessor, as Heller and Farrell sought to recombine their talents in the cause of helping Aldrich bring to the screen an unpublished sort-of semi-sequel short story (originally titled, with obvious self-awareness, Whatever Happened to Cousin Charlotte?) that Farrell had written to be made as another one of Robert Aldrich's independent productions, but on a considerably larger budget than had been available for Baby Jane.

For reasons now more widely understood (and which furnish a great deal of the ample background material one will find related in fascinating detail by Kat Ellinger and Glen Erickson across the two commentary tracks included with this new Masters of Cinema release), the proposed ‘rematch’ between Davis and Crawford never materialised, Crawford’s supposed health issues apparently necessitating her removal from the production. Fascinating production stills, taken during the shooting of now-missing footage shot before Crawford left the picture, and which show the actress made-up and appearing in character as Miriam Deering, do still exist and display her very different take on a role that was eventually filled by Davis’s colleague Olivia de Havilland. Instead, free of the constant circus of speculation that surrounded the relationship between these infamous Hollywood rivals, Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte emerges as nothing so much as a lavish-looking Southern Gothic spin on the mini-Hitchcock thrillers that Hammer Films had been knocking out on a regular basis for some time by this point, a cycle which had started with Jimmy Sangster’s screenplay for Seth Holt’s Taste of Fear in 1961. Convoluted Gaslight mimicking narratives and endless permutations on the plot to Henri Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques are what drive most of these films, and Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte turns out to be no exception, despite being much more handsomely mounted and exquisitely photographed than anything Hammer -- for all the studio’s brilliance -- could ever have hoped to replicate, even in its heyday.

With its generously sprawling 133-minute full feature length, Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte has more than enough time on its hands to cover quite a few other bases as well: among them out-and-out exploitation and shock imagery. The film racked up an impressive seven Academy Award nominations. But it’s a safe bet to assume that no other Oscar-nominated film in 1964 (and not many others thereafter) featured explicit shots of limbs being bloodily lopped off with a hatchet, or a decapitated head tumbling down a spiral staircase in an antebellum-era-built Louisiana mansion: just two of the film’s main selling points amid a whole suite of gloriously torrid horror theatrics initially disguised by the film’s prestigious cast of Hollywood greats and beautifully lush Southern locations. The film is intentionally constructed from a vast mosaic of cinematic signifiers which are deployed in this case to enable it to straddle the murky grey area that separates B movie hokum from the Hollywood prestige project without ever having to come to a decision about which of these modes should ultimately get to define it. The screenplay is seemingly precision-tooled to evoke every Southern Gothic motif under the sun and, more pertinently, details of narrative, production design, art direction and even the actual casting, conjure at every turn formless ghosts that hint at many instances of Hollywood’s representation of the Deep South on film: having Bette Davis play a fading Southern Belle traumatised by an incident from the past that robbed her of her one chance at happiness might be assumed a reference to the kinds of roles the actress played in her younger days, when she was quite often cast as characters from a similar milieu, such as in the 1938 film Jezebel, for instance; while casting Crawford’s replacement with Gone with the Wind star Olivia de Havilland simply reminds the viewer that Davis also lost out on the role of Scarlett O’Hara to de Havilland’s co-star Vivian Lee.

The film begins with a 1927-set prologue that initially plays like a stage-bound scene from some sultry Tennessee Williams play or other: two characters on a single set confronting each other over the heavy oak desk in the study of formidable Louisiana plantation owner 'Big' Sam Hollis (Victor Buono) on a hot summer night in New Orleans, strains of jazz discernible in the distance from a party that’s in full swing elsewhere in and around the colonnaded mansion and its oak-studded grounds. Baby Jane star Buono’s interlocutor is the young Bruce Dern -- here in an early role following a brief appearance in Hitchcock’s Marnie the year before – who is tasked by the screenplay with the plot-instigating duty of getting himself blackmailed and then becoming an instant murder victim, whose death thereafter haunts the central character for the rest of the film. His name is John Mayhew: the married lover of Hollis’s young daughter Charlotte (Bette Davis). The couple had been planning to elope together on this very night, but their plans have just been exposed and thwarted after Mayhew’s wife Jewel (Mary Astor) somehow got wind of it and told Charlotte’s father. Under pressure from the overbearing patriarch, Mayhew later that night breaks off the elopement with Charlotte in the summer house, leaving her heartbroken. Not long after he is dispatched in the grisly fashion already alluded to. The young Charlotte Hollis, the lower portion of her party dress stained red with her lover’s blood, then wanders semi-comatose into the crowded ballroom of the Hollis mansion, confronting her father and all his guests with this menstrual symbol of the family shame.

Did she kill Mayhew or was the deed done by her overbearing father? Thirty-five years later and the locals of Hollisport continue to debate the macabre legend which has grown up around the lurid events that took place in the home of the reclusive Charlotte Hollis all those years ago. The ageing occupant now lives on the site of the former plantation like the Miss Havisham of Baton Rouge: quite alone apart from her dishevelled housekeeper Velma (Agnes Moorehead) who devotedly tends to her needs and sees off any troublesome trespassers. Pining for her dead love, Charlotte Hollis is believed by most to be mad; children might dare each other to sneak into the old mansion at night, but those who attempt such a feat are liable to find not an axe murderer but only a disorientated old lady in white, still clutching at a box that just might contain the head of her dead lover … or perhaps, maybe, it's the music box Mayhew gifted her thirty years ago, that plays the song he wrote for them both. There is the common suspicion within the community, though, that Charlotte herself was Mayhew’s murderer, and that she has been protected from punishment all these years by her late father’s influence and power, which still seems to exert itself from beyond the grave even now.

The fabulous location exteriors used for Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte play an instrumental role in imbuing the film with the requisite sense of faded historical grandeur, crucial in conveying the latent idea that sins of the past once obscured by these stately residues of a supposedly more genteel age are only now being exposed to light again, as the past crumbles or is forgotten. The plantation owners of the 18th and 19th centuries built their grand homes with those imposing upper balconies and columned porticos, in a neo-classical Greek Revival style intending to associate themselves with the great splendours of a former European civilisation. But the history the architecture of the Antebellum now represents to most of us is, of course, also marked by a darker side: the fact that its beauty was founded on the prevalence of slavery as a tool for economic dominance and social oppression. Charlotte Hollis lives in an anachronistic museum commemorating the historic brutality of this ‘golden’ age once presided over by her late father and his immediate ancestors, and given actual form in the historically preserved location of the 1840s plantation house Houmas House in Burnside, Louisiana that was used for the exteriors -- one of the grandest of its design. In the present day, Charlotte has herself practically become a ghost from this vanished age. Never having come to terms with the belief that her father was responsible for John Mayhew’s murder, she remains frozen in the shock and grief of that immediate moment from all these years ago, only being spurred into action when her family home is threatened with demolition to make way for a new highway. Even more ambiguous a commentary on the shadow of the past is a scene that comes halfway through the film, in which the kindly insurance investigator who takes pity on Charlotte, Harry Wills (Cecil Kellaway), takes tea in the grounds of the house owned by Charlotte’s great rival, the ageing Jewel Mayhew (Mary Astor), and talks with her about that fateful night many years ago when Jewel’s philandering husband was decapitated in the summer house at the Hollis mansion. Aldrich uses as the backdrop to their talk the picturesque sight of a canopied oak allée from the Oak Alley Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana: a location so exquisitely designed to fit a romantic view of the past one would almost have assumed it to be a matte-painted background created specifically for the purpose of conveying that impression. The film is all about the prevalence of masks, and the most deceptive mask is the mask of nostalgia: it cloaks all manner of ills in the soothing afterglow of best intentions and whitewashed motives.

While the historical authenticity of the exterior locations allows the film to become infused with an atmosphere of stately decay and moral ambiguity, the studio-created interiors and the way they are staged, dressed and shot by Aldrich and his repertory company of regular crew members, attest to the continued potency of Gothic horror and its macabre genre offshoots. Art director William Glasgow and cinematographer Joseph Biroc are primarily responsible for creating the rich velvety high-end noir atmosphere enveloping the ornate décor of Hollis House, while costume designer Norma Koch puts the older Bette Davis in platted pigtails and flowing nightgowns to emphasise how the character of Charlotte is trapped in her youthful past even as she plays out the role of a traditional Gothic heroine. Davis gives another committed full-throttle performance that holds nothing back: she may not get to be as demonstrably evil-hearted as she was in Baby Jane but a good portion of the film requires her to inhabit various stages of insanity as visitations and hallucinations of severed heads bouncing down the staircase and-the-like begin tormenting her one by one, as does some ghostly harpsichord music that plays in the night and an encounter with faceless guests in a dreamlike slow-mo ballroom sequence recalling her last night with Mayhew. Frank De Vol’s music once again strikes a fine balance between saccharine irony and sweeping melodrama, particularly on the title song (a rival to Baby Jane’s I’ve Written A Letter to Daddy) which serves multiple roles in the film: one minute functioning as the creepy music box motif associated with Charlotte, and the next as an eerie harpsichord air to signify her final descent into madness. It later also transformed itself chameleon-like into a pop hit of the day for Patti "(How Much Is That) Doggie in the Window" Page!

The fabulous location exteriors used for Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte play an instrumental role in imbuing the film with the requisite sense of faded historical grandeur, crucial in conveying the latent idea that sins of the past once obscured by these stately residues of a supposedly more genteel age are only now being exposed to light again, as the past crumbles or is forgotten. The plantation owners of the 18th and 19th centuries built their grand homes with those imposing upper balconies and columned porticos, in a neo-classical Greek Revival style intending to associate themselves with the great splendours of a former European civilisation. But the history the architecture of the Antebellum now represents to most of us is, of course, also marked by a darker side: the fact that its beauty was founded on the prevalence of slavery as a tool for economic dominance and social oppression. Charlotte Hollis lives in an anachronistic museum commemorating the historic brutality of this ‘golden’ age once presided over by her late father and his immediate ancestors, and given actual form in the historically preserved location of the 1840s plantation house Houmas House in Burnside, Louisiana that was used for the exteriors -- one of the grandest of its design. In the present day, Charlotte has herself practically become a ghost from this vanished age. Never having come to terms with the belief that her father was responsible for John Mayhew’s murder, she remains frozen in the shock and grief of that immediate moment from all these years ago, only being spurred into action when her family home is threatened with demolition to make way for a new highway. Even more ambiguous a commentary on the shadow of the past is a scene that comes halfway through the film, in which the kindly insurance investigator who takes pity on Charlotte, Harry Wills (Cecil Kellaway), takes tea in the grounds of the house owned by Charlotte’s great rival, the ageing Jewel Mayhew (Mary Astor), and talks with her about that fateful night many years ago when Jewel’s philandering husband was decapitated in the summer house at the Hollis mansion. Aldrich uses as the backdrop to their talk the picturesque sight of a canopied oak allée from the Oak Alley Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana: a location so exquisitely designed to fit a romantic view of the past one would almost have assumed it to be a matte-painted background created specifically for the purpose of conveying that impression. The film is all about the prevalence of masks, and the most deceptive mask is the mask of nostalgia: it cloaks all manner of ills in the soothing afterglow of best intentions and whitewashed motives.

While the historical authenticity of the exterior locations allows the film to become infused with an atmosphere of stately decay and moral ambiguity, the studio-created interiors and the way they are staged, dressed and shot by Aldrich and his repertory company of regular crew members, attest to the continued potency of Gothic horror and its macabre genre offshoots. Art director William Glasgow and cinematographer Joseph Biroc are primarily responsible for creating the rich velvety high-end noir atmosphere enveloping the ornate décor of Hollis House, while costume designer Norma Koch puts the older Bette Davis in platted pigtails and flowing nightgowns to emphasise how the character of Charlotte is trapped in her youthful past even as she plays out the role of a traditional Gothic heroine. Davis gives another committed full-throttle performance that holds nothing back: she may not get to be as demonstrably evil-hearted as she was in Baby Jane but a good portion of the film requires her to inhabit various stages of insanity as visitations and hallucinations of severed heads bouncing down the staircase and-the-like begin tormenting her one by one, as does some ghostly harpsichord music that plays in the night and an encounter with faceless guests in a dreamlike slow-mo ballroom sequence recalling her last night with Mayhew. Frank De Vol’s music once again strikes a fine balance between saccharine irony and sweeping melodrama, particularly on the title song (a rival to Baby Jane’s I’ve Written A Letter to Daddy) which serves multiple roles in the film: one minute functioning as the creepy music box motif associated with Charlotte, and the next as an eerie harpsichord air to signify her final descent into madness. It later also transformed itself chameleon-like into a pop hit of the day for Patti "(How Much Is That) Doggie in the Window" Page!

Davis’s florid performance is complemented by an equally robust comic turn from Agnes Moorehead, as muttering maid Velma. A fine character actress who at the time would have been best-known for playing Samantha’s mother Endora on the TV series Bewitched, Moorehead's career stretched back to the 1930s when she did a stint with Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre troupe, performing alongside Joseph Cotten, who now joins her again in this film for a smallish role as Charlotte’s doctor, Drew Bayliss. As the former lover of Miriam Deering, Cotten delivers the required levels of sliminess in a role originally slated to have him play most of his scenes opposite Crawford but which eventually saw him working with Olivia de Havilland instead. The couple’s relationship dates back to the time of John Mayhew’s murder in 1927. Bayliss broke it off back then with Miriam because of the scandal associated with the Hollis name in the wake of Mayhew’s death -- meaning Miriam is returning to a site that holds painful memories not just for cousin Charlotte but for her too. Those memories are made all the more tangible when Miriam comes back to Hollisport at the request of her cousin after years living a metropolitan life in the big city. Charlotte wants her to help in the fight to oppose the building of the highway on the site of the Hollis mansion, but Miriam returns to find that, forty years later, her old lover Bayliss is still the acting family physician. While everyone else appears to be trapped in an emotional time warp by the events of forty years ago, Miriam comes across as a stable, level-headed person who is being forced into confronting the tumult of her past against her will. But of course, this being a Gothic-themed thriller, with all the twists and turns that entails, the truth of the matter proves to be a great deal more complicated. Olivia de Havilland is probably a much better casting choice in that regard than Joan Crawford would have been, since she initially exudes an air of normalcy that makes her a viewer identification figure from early on in the movie: a witness to the madness, eccentricities and abnormalities of all the other characters, and a good steady foil to the exaggerated flightiness of Davis’s character. As the plot unfolds, a harder edge emerges to her Miriam Deering and one of the film’s major strengths lies in the way de Havilland manages her character’s transition from apparently innocent bystander to the prime instigator of some pretty fiendish events. The plot itself might not contain anything truly surprising, and is pretty much boilerplate thriller material but de Havilland gives a fully rounded performance that holds the attention throughout, while Aldrich manages to sell a whole plethora of deranged, surrealistic sequences in the second half that makes the ride entertaining even if we’re never truly in any doubt as to the eventual destination.

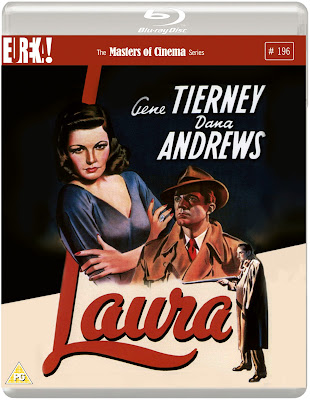

Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte was always a handsome-looking film, and it finally gets a fitting 1080p HD presentation for this UK Blu-ray release from Eureka Entertainment as part of The Masters of Cinema series. A 22-minute archive ‘making of’ featurette contains all the basic background production facts on the film, and Bruce Dern provides a nice 13-minute interview in which he recalls his interactions with Bette Davis on set and behind the scenes. There’s also a brief 5-minute contemporary set report narrated by Joseph Cotten. But the two stand-out commentaries are the main centrepieces of the extras package included here: Kat Ellinger once again proves her worth with a well-researched track that takes a thoughtful look at, among other things, Robert Aldrich’s relationship with the ‘women’s picture’ and the cross-over he forged with noir and Southern Gothic. Meanwhile, Glenn Erickson provides a more traditional overview, concentrating on biographical info about the main cast and crew members. Both contributors tackle the Joan and Bette feud and the drama of Crawford’s replacement by de Havilland, each managing to bring an individual take to the business without contradicting the other on the basic facts. Trailers and TV spots are included, and this Blu-ray only release also comes with the traditional collector’s booklet, this one featuring a new essay by Lee Gambin illustrated with some fascinating archival imagery.

Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte is a gorgeously overwrought piece of Gothic melodrama and a fine example of the mid-sixties ‘twist in the tail’ thriller. It has some great performances from usually side-lined older actresses, while the likes of Joseph Cotten, George Kennedy and Cecil Kellaway are this time relegated to supporting roles. Aldrich gave what could have been considered relatively trivial by-the-numbers material his full directorial attention, creating a lush spectacle of Gothic madness that delves into all manner of twisted psychological unpleasantness with a wilful glee. The cast of Hollywood greats at its centre seems to have been more than happy to follow Aldrich wherever he may lead them, in what has turned out to be a much-overlooked gem of the genre.