Yasujirô Ozu was one of the

most celebrated, idiosyncratic yet -- in his day -- commercially successful

filmmakers in the history of the Japanese film industry. He worked, across nearly

the entirety of his movie-making career, for the Shochiku Company Limited -- the mammoth

studios at

which he first started out as an assistant cameraman in 1923 after

failing his university exams twice. The company was founded in the

late-eighteenth century, initially as a producer of live kabuki theatre; but

it expanded its output to encompass movie production in the 1920s, soon abandoning

the mannered stylisations and all-male yarō-kabuki

conventions of traditional Japanese drama for its own version of the Hollywood

star system during the silent era, which ushered in a mode of narrative

expression much influenced by that which was familiar from American movies of the day, but which was still concerned with portraying the everyday lives of ordinary Japanese

people. Ozu’s work is, of course, renowned for its detailed dissection of family

life, which it achieves through the delicate unwrapping and laying bare of character: the novelistic, in-depth

exploration of inter-generational relationships between Japanese parents and

their children, growing up in a country tinged with regret for a vanishing past even

as it comes to grips with modernity. His work began to develop an appeal

born of the distinctive technical tropes that separated his later approach to the crafts

of filming and editing from the standard visual language adhered to at that

time by almost everybody else working in cinema (both in Japan and abroad)

during the mid-thirties, when he made a silent film called A Story of Floating Weeds (Ukikusa monogatari) – an adaptation

of a 1928 American picture called The

Barker, that had been directed by George Fitzmaurice and starred Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

-- and he continued to perfect and refine his style throughout the Golden Age of

Japanese cinema, creating many masterpieces that only came to the attention

of western audiences in the 1970s. But

it was his late-career colour films which gave full expression to the purest

manifestation of what became known as the

Ozu style.

Yasujirô Ozu was one of the

most celebrated, idiosyncratic yet -- in his day -- commercially successful

filmmakers in the history of the Japanese film industry. He worked, across nearly

the entirety of his movie-making career, for the Shochiku Company Limited -- the mammoth

studios at

which he first started out as an assistant cameraman in 1923 after

failing his university exams twice. The company was founded in the

late-eighteenth century, initially as a producer of live kabuki theatre; but

it expanded its output to encompass movie production in the 1920s, soon abandoning

the mannered stylisations and all-male yarō-kabuki

conventions of traditional Japanese drama for its own version of the Hollywood

star system during the silent era, which ushered in a mode of narrative

expression much influenced by that which was familiar from American movies of the day, but which was still concerned with portraying the everyday lives of ordinary Japanese

people. Ozu’s work is, of course, renowned for its detailed dissection of family

life, which it achieves through the delicate unwrapping and laying bare of character: the novelistic, in-depth

exploration of inter-generational relationships between Japanese parents and

their children, growing up in a country tinged with regret for a vanishing past even

as it comes to grips with modernity. His work began to develop an appeal

born of the distinctive technical tropes that separated his later approach to the crafts

of filming and editing from the standard visual language adhered to at that

time by almost everybody else working in cinema (both in Japan and abroad)

during the mid-thirties, when he made a silent film called A Story of Floating Weeds (Ukikusa monogatari) – an adaptation

of a 1928 American picture called The

Barker, that had been directed by George Fitzmaurice and starred Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

-- and he continued to perfect and refine his style throughout the Golden Age of

Japanese cinema, creating many masterpieces that only came to the attention

of western audiences in the 1970s. But

it was his late-career colour films which gave full expression to the purest

manifestation of what became known as the

Ozu style. One of his very last films was a fully-fledged remake of Ukikusa monogatari, which he shot at the age of fifty-six, just a few years before he died. It was one of the few pictures he made outside the auspices of the Shockiku studio and only his third in colour. Although Ozu’s work always stuck closely to the exploration of the same handful of family-related themes and can in some ways be taken as one project, constantly retold from a variety of angles, Floating Weeds was only the second direct remake of an earlier work, coming in the wake of Good Morning, which had been a reworking of one of his first major films from 1932: A Picture-Book for Grown-Ups: I Was Born, But…. This latest remake broke new ground in many ways though, mainly related to the involvement in its production of the president of Daiei Studios, Masaichi Nagata, who backed the picture after work on it had stalled at Shochiku.

Nagata is one of the most important studio figures active during this period of Japanese filmmaking; he produced Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi just as they were making huge waves on the International festival circuit with Rashômon and Ugetsu Monogatari, and he put into production one of Japan’s most opulent early colour films: Teinosuke Kinugasa’s magnificent Gate of Hell, also an early example of a successful foreign export for Japan's blooming fifties film industry. Nagata’s involvement lent a similarly high profile to Floating Weeds, which required that Ozu work with a different cinematographer from his usual collaborator, Yûharu Atsuta - who beforhand had been almost Ozu’s only photographic partner and who had been instrumental in conceiving the visual look of his films since 1937.

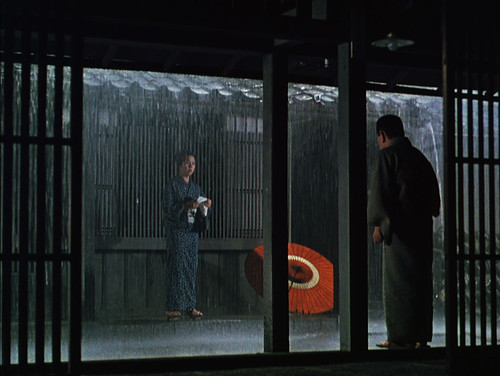

Both men were ‘sceptical’ of the shift to colour photography in the 1950s, and had used it in as understated a way as possible on Ozu's first two colour outings at Shochiku. But now Nagata paired Ozu with Kazuo Miyagawa -- the top cinematographer at Daiei, and the man who had presided over the visuals of both Rashômon and Ugetsu Monogatari. Miyagawa also enthusiastically embraced the possibilities now opened up by the growth of colour photography, and the new collaboration between these two masters of their respective arts (the traditionalist Ozu and the embracer of modern practices Miyagawa) resulted in Floating Weeds emerging as a rich, painterly example of Ozu’s best cinema, bringing new depth and vivid clarity to the director’s spartan sense of film grammar (which had become, by this point, an extremely finely pared aesthetic), but in a way that actually emphasises its stripped down economical nature rather than “tarting it up” with unnecessary dressings ... Although Ozu wasn’t going to capitulate to that other new fifties trend: the craze for CinemaScope - preferring to stick to the traditional “picture-frame” box image familiar to the Academy Ratio - Floating Weeds was a sumptuous spectacle of a film, that nevertheless, employed its colour intelligently and systematically, in selective artistic patterns.

Ozu’s later films come to put

increasingly less and less emphasis on the kind of overtly dramatic events that

normally drive a film’s plot forward. Instead, they base their stories around

the gradual delineation of the relationships between a group of central

characters. The subject matter of Floating Weeds develops out of the arrival,

in a small coastal port town, of a travelling troupe of theatre players led by

its chief actor and employer Komajuro Arashi (Ganjiro Nakamura), during

the stifling heat of the summer of 1958. There is no special effort made in the first act of the film to

draw the viewer’s attention to what will be Komajuro’s importance in the tale

to come: instead, for the first ten minutes,

Ozu follows a set of minor characters who turn out to have little relevance to

the later story, as he lays in place the dynamic governing the behaviour of the

troupe – the itinerant “floating weeds” of the title – and their interactions

with the inhabitants of the town. We see the distribution of pamphlets

advertising the players’ forthcoming programme of traditional kabuki dramas;

and the indifference this arouses in everyone but the town's children - who are

more excited by the arrival of new people in this quiet, sleepy inland port

than by the prospect of the ‘entertainment’ the theatre troupe has to offer.

The members of the troupe themselves, lead a mundane existence between shows:

arriving by ship, packed into its hold in the sweltering heat, the lead female member (this is a modern kabuki troupe

who have re-introduced women performers) chain-smoking furiously as she will be

seen to do throughout most later ‘off-stage’ scenes (women smoking is a sure

visual code sign for abrasiveness in Ozu’s cinema), while the male performers

visit the local brothel to haggle over their choice of prostitute or else

attempt to chat up the local beauties … with little success, given the evident

low regard travelling theatricals are held in here, even by a poor coastal

community.

These initial scenes provide us with an evocative sketch portrait of

the community and its visitors that resonates far beyond the mere handful of

sequences set before us to illustrate it. Gradually, Master Komajuro and his current mistress

Sumiko (played by one of the most recognisable actresses in ‘50s Japanese

cinema, Machiko Kyō) emerge as the key characters in this set-up: Komajuro

assures the town theatre’s impresario (Chishû Ryû) and the players of his own

troupe, that their initially poor audiences will soon pick up as the

season progresses. But the signs are that the particular programme Komajuro and

his players have to offer is these days considered old-fashioned, and their

style of acting thought quaint and ‘hammy’. It also turns out that Komajuro is

preoccupied by other interests in the area: his former mistress, the owner of a

local Sake bar (Haruko Sugimura) lives here with his illegitimate son from their former relationship, Kiyoshi

(Hiroshi Kawaguchi), and Komajuro hasn’t seen

either of them for many years before this latest visit. Komajuro’s visits always

depend on the itinerary of his troupe, and the boy doesn’t even know the true

nature of his connection to a man he calls uncle and thinks of as just a friend

of the family.

The film’s first hour makes fine use

of the poignancy suggested by this situation, as it explores various facets of the

character of each of the three main parties involved in the much older relationship.

Nakamura’s comic displays of over-enthusiasm, which erupt out of his desire to

engage a reticent Kiyoshi in numerous father-son bonding activities -- such as

fishing or endless games of Go (which he plays because Kiyoshi is keen on the

game, not because he has any particular aptitude for it); his need for excuses

to spend his free time with the boy, while being anxious to maintain the secrecy

that surrounds their relationship and not reveal who he really is to his son, makes for a gentle, relaxed form of

humour, etched with regret. Contrasting the precariousness of theatre life via the troupe’s

dependency on achieving a certain degree of popular success with its show in order to

enable Komajuro to earn enough money to be able to afford to move on to the

next town, lest his performers become “stranded” in one place, and setting that situation next to the ‘master’s’

desire also to experience a simulacrum of settled family life, but still always

with the option of one day moving on, bit by bit brings out the sensibilities of each

of the main players: Komajuro’s former mistress Oyoshi, gently appears to

accept the father of her child’s causal, on-off relationship with their son, while harbouring

the secret wish that he will eventually decide to stay put and the three of

them might one day settle down as a proper family. Kiyoshi, meanwhile, ostensibly

unaware of the true basis of of his relationship with his mother’s slightly

eccentric and over-chummy avuncular friend, dreams of leaving the sleepy port

behind, and, with that in mind, is being trained in maths by the local postmaster in preparation for

leaving for university. Unfortunately, the increasing frequency of Komajuro’s absences

from the troupe between shows comes to be noticed by his employees and eventually his current

mistress, Sumiko, learns from one of the veteran actors (who has travelled with

the master on many other sojourns across the country with the troupe, down the years), about Komajuro’s

secret son, and of his former relationship with Oyoshi, the owner of the Sake

drinking joint; jealous and fearful of her own precariousness in this

situation, Sumiko hatches a cynical plot to split up this threateningly cosy

makeshift family unit which potentially threatens the continuation of the troupe and therefore

her own relationship with its owner, by forcing one of the younger, prettier

female performers travelling with the theatre -- an actress called Kayo (Ayako Wakao) -- to seduce Kiyoshi!

The relationship between Kayo

and the virginal Kiyoshi becomes a serious one and the two of them plot to run

away with each other, the previously conscientious Kiyoshi now willingly abandoning

his hard-won studies in order to do so, apparently just as Sumiko had planned

when she came up with the idea to pair the two off as part of her revenge on

her master. A darker side to Komajuro’s nature emerges in the second half of

the film; despite his justified anger at Sumiko’s dirty tricks, his own attempts

to enjoy the benefits of fatherhood without any of its responsibilities don’t always

paint him in the best of lights (even the pliant Oyoshi reminds him that she’s

familiar with his’ crafty’ ways, at one point). The illicit relationship

between the two youngsters also reveals Komajuro’s less than flattering attitude

towards the women who work for him as performers in the kabuki theatre plays:

he speaks of Kiyoshi being “ruined” by the association and of the gentle Kayo as though she were

inherently no better than a whore because of her stage-based profession, and this

naturally leads to the inevitable confrontation between himself and Kiyoshi. Ozu

unfolds this cauldron of previously unvoiced prejudices and emotions in his

traditional un-showy, unmistakably direct yet subtle style, so that these people’s

jealousy, bitterness, regret and self-deception emerges out of the deepest

expressions of his characters' intrinsic being, rather than merely as motors for

pursuing the next stage of a contrived developing action. A stoic melancholy

acceptance of their flaws (and all the characters are flawed in

some way … yet also likable in an almost equal measure at different stages

during the two hours we spend with them) pervades a languid atmosphere, in which

a sad but resilient attitude to the hardships of the present, for characters

caught up in their own version of the past, is amplified by the most

uncompromising version of the Yasujirô Ozu house style – a style which emphasises

continuity through its complete lack of camera movement and rejection of transition effects

for bridging scenes – fades, wipes, dissolves, etc -- leaving the film with a sense of passivity and stasis.

For all the apparent possibilities and expectations for change his characters might share, Ozu’s cinema favours incident over plot, dawning realisation over actual change in circumstances. His stories generally do not move from one set of major events to another, but instead tell of the sadness of time passing or “mano no aware”. The darkening of mood in the second half of the film is implied in the mere texture of the difference between the gentle, pastel shades of colour which are predominant in Kazuo Miyagawa’s cinematography during the unvarying static daytime shots of the film’s first hour, and the bright fabrics of the characters’ kimonos set in a sharp relief against the darkness of the night-time exteriors and candle-lit interiors which dominate the second half. Floating Weeds soon came to be seen as another one of Ozu’s greatest masterpieces and its refined but vivid use of colour photography and art direction brings a whole new angle to the director’s pared down minimalist style, which makes it an ideal place to start for those new to his cinema.

The latest Masters of Cinema release of the title is a dual-format edition combining a DVD copy and a Blu-ray disc in the same package, and features a high definition transfer that provides an authentic rendering of the film for the medium: typically unflashy but a step above most standard definition treatments. The mono sound is a little noisy and quite muddy, but still adequate, and the on-screen removable English sub-titles are clear and literate and of a decent but unobtrusive size. The release is not overburdened with extras (there is only a trailer on the disc itself) but the accompanying thirty-six page booklet contains a very informative and readable essay on the film by film critic Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, called Getting an Angle on Ozu, which examines the pre-production history of the film and provides a convincing analysis of the finished work. There is also a selection of quotations from Ozu’s published diaries included at the back of the booklet.

Floating Weeds is another timeless classic of late Golden Age post-war Japanese cinema, and makes for rewarding viewing in this high quality formatted edition.